Living history: Ģ������Ƶresearchers work to capture Cherokee oral histories

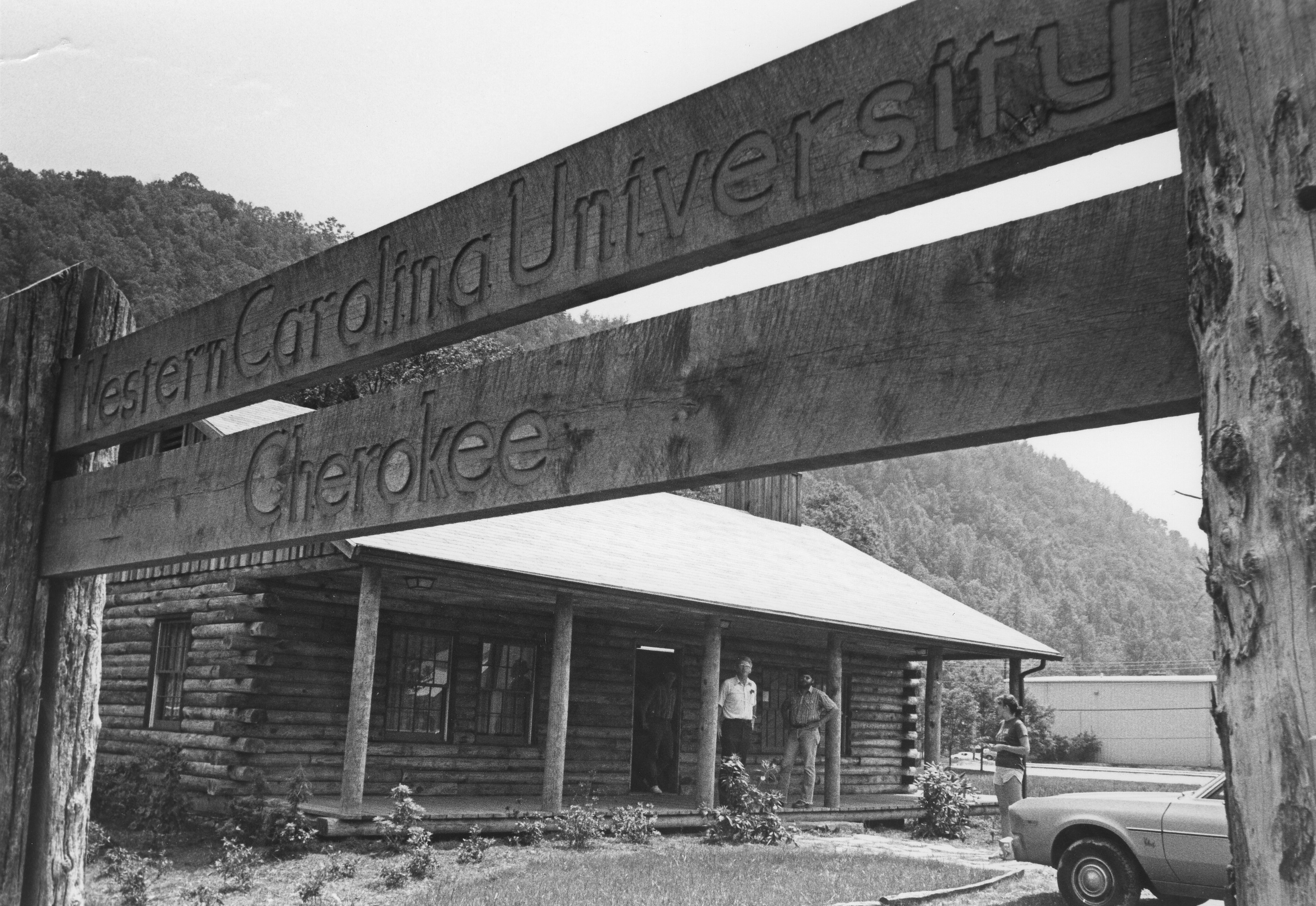

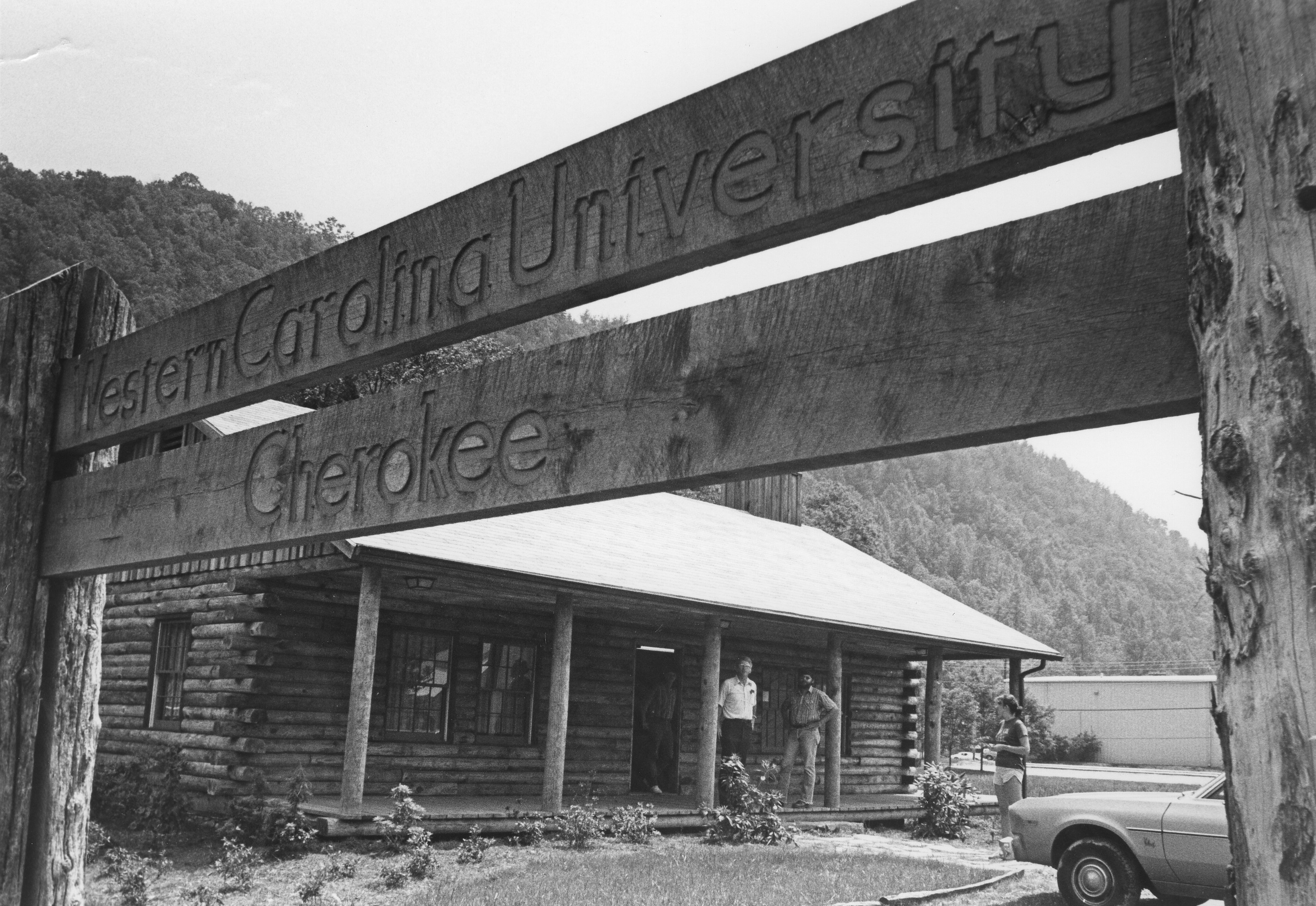

The Cherokee Center in the 1970s

By Shane Ryden

The history of Ģ������Ƶ is held by its people. Though archives and images can provide a framework for the past, there is no richer or truer contribution to the story than the lived experiences of alumni, staff, faculty and students.

As part of a broader university history project and in anticipation of the 50th anniversary of WCU’s Cherokee Center this fall, faculty scholars and graduate students on campus have begun conducting oral history interviews of Cherokee alumni.

Their goal, though broad, is simple: to capture the indigenous experiences of those who work and study at Ģ������Ƶand to better understand the dynamic relationship between the university and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

Joyce Dugan speaks during the opening ceremony of Judaculla Hall

Elizabeth McRae, WCU’s graduate director of history, described how an oral history interview she conducted in the summer of 2024 with Joyce Dugan, former principal chief of the EBCI, alumna and Ģ������ƵBoard of Trustees member, inspired and gave direction to their research.

“In that conversation about her relationship with Western over the years, she suggested that we speak with Cherokee citizens about their relationship to Western, their education, their service to Western, the changing nature of that relationship,” McRae said.

“It is upon her suggestion that we decided to make Cherokee studies and the oral history project about Cherokee at Ģ������Ƶthe next iteration of the project.”

Andrew Denson, WCU’s director of Cherokee studies, was eager to collaborate, understanding the limitations that larger institutions face in documenting their fleeting present.

Participants learn basket weaving at the Mountain Heritage Center in 2006

“Our university records will give you a picture of the institutional history,” Denson said, “but they won’t necessarily give you a sense of how students experience campus or how and where various initiatives really come from, like what sort of human motivation or immediate circumstance were to, for example, launch the Cherokee language program 15 years ago.

“Institutions will often give you a top-down picture of their functioning…What oral history allows you to do is much more of an individual or bottom-up look at how a community or an institution operates.”

The research inspires questions that will shape the years to come, Denson described:

“How can the university better serve this place and the communities in Western North Carolina? History can be part of that because things like oral history projects allow you to reflect on that and give you this space where we can think about what has worked, what hasn’t worked in the past and then what the possibilities are in the future,” Denson said.

“We always say that our initiatives as academics need to come out of serving the needs of Indigenous communities.”

Denson and McRae employed the help of a number of graduate students in the project to assist with conducting and transcribing interviews.

Participants during a past Rock Your Mocs event on campus

“I think it’s really an extraordinary opportunity for our graduate students to participate in the creation of an archive of a wide range of people’s experiences and memories and relationships with Ģ������Ƶ,” McRae said.

Their questions explore their interviewees’ time on campus and their general feelings on the relationship between Ģ������Ƶand the EBCI. The recordings produced will eventually be archived in Hunter Library.

“It’s one thing to sit in a classroom and be told ‘here is how you do good oral histories,’” said Celeste McCall, graduate student of public history, “and it’s another thing entirely to be out in the world doing that.”

For McCall, the project has offered an intriguing and intimate opportunity to engage with the techniques she’s garnered over the course of her career at WCU.

“It’s something very unique, because I think it has the opportunity to make history real for more people, because they’re listening to someone describe something in their own words instead of just reading about it in a textbook. You’re getting the emotions at a more personal level.”

Another graduate student of history, Rachel Lam, expressed her excitement at her program’s consistent and thorough attention to Cherokee scholarship.

“Ģ������Ƶhas consistently had some of the top Cherokee studies scholars on faculty in the country for decades, and so many Cherokee leaders have attended Ģ������Ƶ(like Joyce Dugan, who received both her bachelor of science and master of science here and later became the first female principal chief of the EBCI),” Lam said.

“Highlighting both Cherokee alumni and Cherokee studies scholars who have helped WCU become an important hub for Cherokee thought is a fantastic celebration of what makes Ģ������Ƶso amazing today!”

Driver Blythe

Driver Blythe, graduate student of history and first-ever Indigenous Ģ������Ƶcommencement speaker, was among those interviewed for the project.

“I enjoyed reflecting on my relationship with WCU,” Blythe said. “I hope to continue being a part of the university after I graduate from my master’s program and continue to learn from the phenomenal instructors at Ģ������Ƶin some capacity.

“We have the most caring professors who are passionate about what they teach and genuinely care about their students’ concerns. Ģ������Ƶisn’t just a college to me, it’s also a homecoming in a way, as it is on ancestral land of my tribe, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. I feel more at home here than anywhere else when it comes to education.”

Blythe described being honored to be a part of the formal archive and expressed his hopes that in sharing his story, other Indigenous students will take advantage of those opportunities available to them at WCU.

“I chose to participate in this interview as possibility to inspire other students, especially indigenous students, to shoot for their dreams of establishing their names,” Blythe said.

“By establishing your name, you establish your tribe as well. Take pride in who you are and remember that nobody can take your hard-earned accomplishments from you.”

Melissa Wargo, chief of staff for Ģ������ƵChancellor Kelli R. Brown, and Carol Burton, vice provost of academic affairs, helped launch the university’s broader research project and assisted Cherokee researchers by coordinating funding and support.

Both Wargo and Burton have also had a hand in organizing the 50th anniversary celebration of WCU’s Cherokee Center, a crucial arm of the university which has greatly contributed to the partnership between members of the EBCI and WCU.

Unveiling of the Cherokee Masks display in the A.K. Hinds University Center in 2004

“I think it’s just a real testament to how much the relationship with the Cherokee, especially the Eastern Band, has become part of the identity of Western, and I think that’s worthy of celebration,” Wargo said.

“We all have pride in this region of western North Carolina and its history, and we want to preserve that, so people know how we came to be.”

Burton echoed her sentiments on the subject with a hopeful vision for future such celebrations and investigations of the bond.

“Our students, faculty and staff are deeply appreciative of the generations of strong relationships with the Cherokee and look forward to the next 50 years of collaboration and community relationships fostered by the work of the Cherokee Center,” she said.